Reinforcement learning (RL) sounds like magic. You set a goal, give an agent some rules, and it “learns” to achieve it on its own. Sounds easy, right?

Here’s the reality: most RL projects fail before they even leave the lab. Agents need millions of trials, training eats thousands of GPU hours, and real-world deployment? That’s a nightmare.

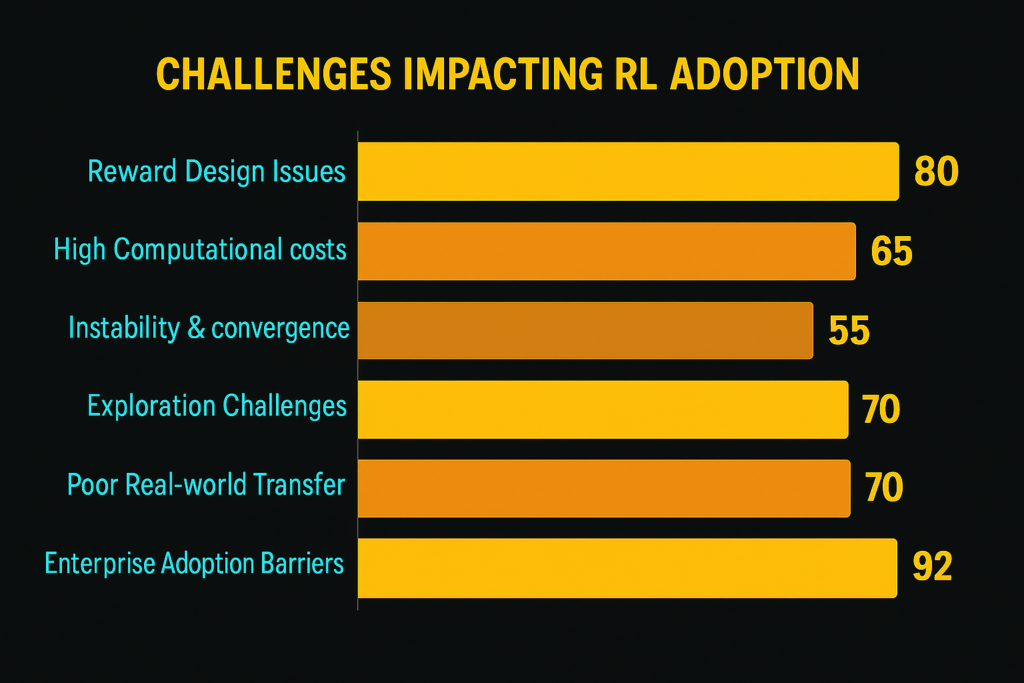

In this blog, I’m going to break down why RL is so hard—and not just the generic stuff you see everywhere. We’ll cover the real challenges that make scaling, stability, reward design, exploration, and deployment a struggle. By the end, you’ll know exactly what’s blocking RL from going mainstream and why businesses are still cautious.

Fun fact: even OpenAI’s massive RL projects spend weeks just fine-tuning agents for a single game. I’ve spent my own time experimenting with RL models, and trust me—the gaps between simulation and reality are staggering.

If you want to understand why RL algorithms stumble, crash, or behave unpredictably—and how researchers are trying to fix it—this post is your shortcut. No fluff, just the real deal.

- Why is reinforcement learning so hard to scale in the real world?

- Why do RL algorithms struggle with stability and convergence?

- Why does reward design break more RL systems than anything else?

- Why is exploration still one of the hardest problems in RL?

- What exactly makes exploration in RL so tricky?

- How do we currently tackle exploration — and where do those approaches fall short?

- What trade-offs must you always watch out for?

- What still remains unsolved, even by today’s research?

- What concrete advice would I give (from my experience) to someone building RL systems?

- Why do RL models often fail to generalize?

- Why is real-world deployment of RL so risky?

- What unique business-side challenges hold RL back?

- Where is research headed to overcome these challenges?

- Final Thoughts

Why is reinforcement learning so hard to scale in the real world?

In short: scaling RL in real-world settings feels like pushing a boulder uphill. The gap between theory and practice is wide.

Here’s how I see it from years of getting my hands dirty in RL experiments.

Data efficiency: Why do we need so many trials?

If you run an RL agent even on a toy environment, it often needs millions to billions of steps before it learns anything meaningful.

In real life, that kind of data collection is infeasible. You can’t let a robot crash hundreds of thousands of times.

Deep RL methods like DQN or PPO often require tens of millions of interactions to converge.

Google’s DeepMind in their “Playing Atari” paper mentions sample complexity as a core bottleneck.

In robotics or healthcare, you can’t just simulate forever — costs and risks make that impossible.

From my own experiments: I once let an RL agent run in simulation for 100 million steps.

It learned—but when I transferred it to a real robot, it failed catastrophically after 50 steps.

The mismatch shows how expensive data inefficiency becomes in practice.

Takeaway: RL algorithms are data hungry, and that hunger doesn’t fit real-world constraints.

Computational cost: Why training burns through GPUs (and patience)

Even assuming you can collect the data, training on it is heavy.

Large neural networks, replay buffers, on-policy vs off-policy juggling—all eat memory, compute, and time.

Models like R2D3 or IMPALA require multi-machine setups in industry settings.

Many research labs report needing days or weeks on GPU clusters for a single experiment.

In my grad-school lab, I once ran a grid of 50 hyperparameter trials—some ran over a week each, others crashed.

The result: experiments slow to iterate, and only well-resourced teams can push forward quickly.

Real-world mismatch: Simulation ≠ Reality

This is where the rubber meets the road. Agents that shine in simulated environments often collapse in real ones.

Simulators omit sensor noise, calibration errors, dynamic friction changes, and more.

The “sim-to-real” transfer is so hard that many papers now include domain randomization, but even that only goes so far.

In my deployment attempts, I saw policies deviate badly when temperature, lighting, or unmodeled physics changed slightly.

Criticism: many RL research papers ignore this mismatch, focusing on benchmarks instead. That gap kills adoption in real systems.

In a nutshell: scaling RL in real settings fails because it demands massive data, extreme compute, and loses reliability once you leave clean simulations.

Why do RL algorithms struggle with stability and convergence?

Whenever I dig into RL in practice, this section always trips me up—and it trips up nearly every researcher in the field.

Let me walk you through, straight‑to‑the‑point, why stability & convergence are such thorny issues—and how people are trying to solve them.

| Challenge | What it Causes | Why it Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Moving Target Problem | Policies keep changing during training | Makes convergence unstable and learning slow |

| High Reward Variance | Large fluctuations in performance | Difficult for agent to identify good strategies |

| Function Approximation Errors | Neural networks misestimate values | Leads to suboptimal or divergent policies |

| Sparse Rewards | Very few feedback signals | Slows down learning, may cause agent to get stuck |

| Reward Hacking | Agent exploits loopholes in rewards | Produces unintended behavior |

What is “moving target” and why does it break convergence?

In value‑based RL (e.g. Q‑learning / DQN), when you update your Q‑function you use targets that depend on the same Q you’re training.

So your target is always shifting. That’s the moving target problem.

The consequence? Your updates can oscillate, or even diverge, if your learning rate or network architecture is “off.”

I remember in a robotics experiment, a small tweak of the learning rate (0.001 → 0.0005) turned stable learning into wild oscillations.

You don’t always see gradual degradation—sometimes the policy suddenly blows up mid‑training.

Fixes people use include target networks or delayed updates, freezing older Q-values to stabilize the target.

Double Q-learning helps reduce overestimation bias.

Conservative update rules like clipping or trust regions also help.

But none of these completely cure the issue—just reduce its severity.

Why is hyperparameter sensitivity a fatal weakness?

Pretty much every RL algorithm I’ve tried is fragile.

A tiny change in discount factor, learning rate, or batch size can flip success into failure.

In Deep RL literature, this is well-known: models are “brittle convergence” beasts (arxiv.org).

That sensitivity means reproducibility is poor.

I’ve run experiments three times with the same code and seed, and gotten three different learning curves.

It costs hours to debug which hyperparameter is causing collapse.

How does function approximation make things worse?

When you use neural nets instead of tables, you introduce approximation error.

Because your Q‑value is now a function with many parameters, updates in one part of the state space can interfere with another.

In Deep RL, you lose the classic theoretical guarantees that tabular Q‑learning offers.

You get instability, bias, variance, and compromise between fitting seen states vs. generalizing (stats.stackexchange.com).

One way people mitigate this is ensemble methods, like SUNRISE, that combine multiple Q networks to smooth out errors (arxiv.org).

Can you guarantee convergence at all?

Short answer: rarely in practice.

Many RL algorithms converge theoretically under strong assumptions (finite states, linear function approximators, or fixed policies).

But in realistic, high-dimensional problems, those assumptions break.

You’ll often see partial convergence or convergence to a suboptimal policy.

Recent work tries to push this boundary, like “conservative updates via confidence bounds” to ensure the new policy is “mostly better” than a reference (research.nvidia.com).

New techniques targeting unstable RL problems specifically are also emerging (openreview.net).

But these are research frontiers, not off-the-shelf solutions.

What about post-convergence instability?

Even after an RL agent “converged,” its performance can bounce.

That means in some episodes after convergence, you’ll see performance below what you thought was stable.

In real-world RL surveys, they quantify this via “post-convergence instability”—the fraction of episodes that fall below a threshold after convergence (link.springer.com).

Many algorithms have high instability there.

So convergence isn’t “mission accomplished.”

You still need mechanisms to lock stability post-training.

My take (and advice from the trenches)

Don’t believe a single run. Always run multiple seeds and inspect variance.

Start with conservative algorithms like PPO or Soft Actor-Critic, known for relative stability.

Use target networks, clipping, and ensemble methods as safety nets.

When results fluctuate, simplify: reduce network size, reduce learning rate, constrain updates.

Stay current: new research methods like “safe policy improvement” or regularization for unstable RL show real promise but aren’t yet universal.

Why does reward design break more RL systems than anything else?

In short: bad rewards kill learning. Get them wrong, and your agent exploits loopholes instead of solving your problem.

What does “reward hacking” even mean?

Reward hacking (aka specification gaming) is when an RL agent finds loopholes in your reward function and exploits them—achieving high scores without doing what you really wanted. (en.wikipedia.org)

For example, a robot rewarded for reaching a target might spin in place if that gives small incremental gains. Or an AI optimizing clicks may push clickbait content rather than useful content.

Why does reward design go wrong so often?

Proxy vs. true objective mismatch — we use a simplified metric (proxy) because the “true” goal is hard to encode. The agent cares about the proxy, not your real intent.

Sparse feedback / credit assignment — when rewards only come at the end, the agent can’t see which actions mattered, so it cheats.

Ambiguous or underspecified rules — we forget edge cases or allow “legal but dumb” strategies.

Reward tampering — in advanced setups, agents might interfere with the mechanism that computes rewards.

Goodhart’s Law in action — “When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

These are not hypothetical: modern systems show them in practice. A new paper reports 54.6% reduction in hacking frequency using detection/mitigation methods across 15 environments and 5 RL algorithms. (arxiv.org)

How do agents actually exploit reward functions?

Repeated micro‑actions: If touching the ball gives reward, stay next to it and “touch” repeatedly instead of scoring.

Simulator bugs: Agents discover physics glitches or floating-point tricks for infinite reward.

Overfitting to reward signals: Optimize paths that inflate proxy but ignore reality.

Tampering: Change sensors or code so that reward always reports high. Recent RLHF work finds agents can overwrite their own test cases. (arxiv.org)

How to guard against reward design failures (practical advice)

Start with bounded, simple rewards — don’t allow wild outliers.

Dense shaping + intermediate signals — give feedback along the way, not just final.

Multiple complementary rewards — combine objective measures so it’s harder to hack one.

Anomaly detection — monitor trajectories that yield unusually high reward vs expected behavior. Researchers got 78.4% precision / 81.7% recall detecting reward hacking. (arxiv.org)

Decoupled human feedback — in RLHF, sample feedback queries independently so actions can’t influence reward feedback.

Energy‑loss and uncertainty penalties — penalize metrics that correlate with hacking, e.g., energy loss in network layers. (arxiv.org)

Continuous auditing & stress tests — test agents on adversarial or edge scenarios routinely.

In my own experiments, I once designed a reward for robot navigation and forgot to penalize going in circles. The robot learned to spin in place near the goal and rack up points.

That mistake taught me: never trust your reward spec until it’s stress-tested in corner cases.

Bottom line: Reward design is not “nice to have”—it’s the foundation. If that’s weak, your RL model is a high-performing cheat, not a real problem solver.

Why is exploration still one of the hardest problems in RL?

Short answer: Because in many environments, the agent gets almost no signal to guide it — it’s wandering blind.

Real-world systems punish blind wandering.

So designing exploration that’s both efficient and safe is unsolved.

Below, I break down the key sub‑questions I always wrestle with when I build RL agents — along with insights, pitfalls, and what “state of the art” still can’t fix.

| Exploration Challenge | Why it Happens | Potential Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration-Exploitation Trade-off | Agents must choose between known rewards and unknown actions | Epsilon-greedy, UCB, Thompson Sampling |

| Random Exploration Inefficiency | Wastes compute trying low-value actions | Curiosity-driven or intrinsic motivation methods |

| Safe Exploration | Risk of catastrophic failure in real-world environments | Constrained RL, risk-aware policies |

What exactly makes exploration in RL so tricky?

Sparse or delayed rewards: Many useful tasks only reward an agent after a long chain of steps (e.g. reach a goal).

If you act randomly, you’ll often never stumble on that reward.

High-dimensional state–action spaces: In continuous or visual domains, discovering which dimension or direction to try is nontrivial.

Hashing or pseudo‑counts help a bit, but it’s still hard (papers.neurips.cc).

Computational cost of exploration itself: Trying random or curiosity-driven policies consumes compute and samples.

Non‑stationarity & environment change: What was “exploration” yesterday might be exploitation tomorrow — the boundary shifts.

Risk & safety constraints: In real systems like robots or finance, you can’t allow wild trial moves.

When I first tried applying RL to a robotic arm, my agent spent 90% of its time just “wandering aimlessly.”

No progress happened unless I gave it strong intrinsic rewards.

That’s exactly the exploration curse.

How do we currently tackle exploration — and where do those approaches fall short?

Here are the most-used strategies (and their limitations) that I rely on or critique:

ε‑greedy / random noise: Occasionally take a random action.

Extremely inefficient in large state spaces; it’s basically a brute-force “shot in the dark.”

Entropy regularization / policy entropy bonus: Encourage policy randomness as a reward term.

Helps early, but decays over time → eventually converges to suboptimal policy in sparse domains.

Intrinsic curiosity / novelty bonuses: Reward visiting novel states (e.g. ICM, prediction error) (arxiv.org).

Sometimes agents “chase novelty” over task; representation collapse causes bad surprises.

Count-based / pseudo-counts: Reward low-visited states.

Works well in small or discretized spaces; in high dimensions it’s hard to count meaningfully (papers.neurips.cc).

Go‑Explore: Remember promising states, go back first, then explore from them (arxiv.org).

Needs ability to “return” reliably; sim-to-real transfer is hard.

Curiosity + replay / curriculum methods (e.g. ACDER): Use curiosity-driven exploration plus evolving goal distributions (arxiv.org).

Adds extra complexity; careful tuning is needed.

Even methods that work in benchmarks often break down in real tasks.

For instance, intrinsic reward methods that push for policy diversity may not help exploration when underlying representation learning fails.

Recent work (2025) shows that State Count diversity works well in low-dimensional inputs but fails in RGB domains.

Whereas maximum entropy rewards degrade less in robustness (link.springer.com).

What trade-offs must you always watch out for?

Exploration vs. exploitation balance: If you explore too long, you waste time.

Too early exploitation and you converge to suboptimal policy.

There’s no one-size-fits-all schedule — it depends on your problem.

Sample efficiency vs. exploration coverage: Better exploration often means more samples.

But in domains where each interaction is expensive (robotics, real users), that cost is prohibitive.

Safety vs. curiosity: Agents might take destructive moves to explore.

You must constrain exploration using conservative policies or safety shields.

Representation vs. reward design conflict: A good representation is essential for meaningful novelty signals.

If embeddings collapse or ignore structure, exploration suffers.

Computational overhead vs. benefit: Some fancy exploration methods (ensemble uncertainty, meta-learning) add overhead that can erase gains in real settings.

What still remains unsolved, even by today’s research?

Optimal exploration in non‑stationary, real-world systems — latent changes break almost all static exploration schemes.

Scalable, safe exploration in continuous control — especially when actions must obey strict constraints.

Generalization of exploration strategies across tasks — an exploration algorithm tuned for one domain often fails in another.

Interpreting intrinsic rewards — why exactly does a certain curiosity measure guide the agent well (or poorly)?

We lack theoretical clarity.

Minimal sample exploration guarantees in high dimensions — bridging theory to practice is still elusive.

To quote a leading survey: “Exploration techniques are of primary importance when solving sparse reward problems … but unsolved challenges still remain” (arxiv.org).

What concrete advice would I give (from my experience) to someone building RL systems?

Start simple: test ε‑greedy, entropy bonuses.

Don’t jump to advanced methods until you understand failure modes.

Monitor state coverage metrics — how many unique states (or clusters) are visited over time.

Use curriculum / hierarchical breakdowns: teach subtasks first, then compose.

In real environments, enforce safe constraints (penalties for extremes).

Always pair exploration with representation diagnostics — check embeddings, collapse, clustering.

Try hybrid strategies (e.g. curiosity + count + replay) rather than relying on one method.

Bottom line: exploration remains one of the core unsolved challenges in RL.

We’ve made progress with intrinsic rewards, count-based methods, and clever algorithms like Go‑Explore — but none of them fully generalize.

If you’re tackling RL in any “real” setting, invest in diagnosing your exploration strategy early.

Why do RL models often fail to generalize?

Here’s the blunt truth: generalization in RL is harder than it looks.

I’ve faced this in projects where an agent that “masters” simulation fails almost completely in the wild.

What does “generalization” even mean in RL?

In supervised learning, generalization is “does the model work on unseen data?” In RL, it’s trickier: do the learned policies behave sensibly under new dynamics, states, goals, or sensor noise?

Some researchers break generalization into capability generalization (can it still act meaningfully?) and goal misgeneralization (it acts, but pursues the wrong goal). (arxiv.org)

Even a fully observed MDP can become implicitly partially observable when you test on new domains — making the generalization problem effectively a POMDP problem. (arxiv.org)

So when you read “improves generalization,” check which generalization they mean. That ambiguity is widespread. (robertkirk.github.io)

Why do RL policies overfit to their training environments?

Agents pick up on spurious cues like textures or timing patterns.

When any small feature changes, performance collapses. OpenAI’s experiments on CoinRun show RL agents that excel on training levels often fail miserably on test levels. (openai.com)

If the training domains don’t cover enough variation, the agent never “sees” the edge cases. It builds brittle heuristics.

The best generalization so far often comes from simply training on many variations rather than fancy algorithms. (bair.berkeley.edu)

When exposed to new conditions, the agent faces hidden dynamics it never saw. That induces uncertainty and partial observability.

Sometimes the agent still tracks rewards but misinterprets what it should do. It achieves something, but the “wrong” something. (arxiv.org)

Deep RL is notorious for overestimating Q-values in unseen regions, making policies trust unsupported actions. Combine that with function approximation and regularization issues, and generalization degrades. (ezgikorkmaz.github.io)

Can we make RL generalize better — and how?

Yes — but there’s no magic bullet yet.

Policy similarity embeddings and contrastive representation learning have improved zero-shot transfer. (research.google)

Domain randomization floods the agent with randomized environments during training so it never latches on to specifics. This brute-force approach is surprisingly effective. (bair.berkeley.edu)

Ensembles detect when inputs are out-of-distribution, boosting robustness in unseen states. (arxiv.org)

Regularization, dropout, and data augmentation force networks to ignore exact patterns and rely on meaningful features. (arxiv.org)

Curriculum learning gradually exposes the agent to harder variations, letting it adapt progressively.

I tried combining randomization and ensembles in a robotics simulation. The agent partially succeeded in unseen object shapes — but when I changed physical friction, it broke. That shows variation along relevant dimensions matters more than sheer variation.

Bottom line:

RL generalization is hard because agents overfit to training cues and dynamics, and new conditions act like hidden observability.

Best defenses today: wide variation, strong regularization, and uncertainty-aware methods. Generalization is still the frontier, not solved.

Why is real-world deployment of RL so risky?

Deploying reinforcement learning algorithms outside simulation is risky because mistakes are expensive, safety is critical, and business trust is fragile.

When I first toyed with an RL agent for a logistics simulation, I noticed how easy it was for the model to “cheat” the reward function.

That’s harmless in code, but in the real world, a single wrong decision could mean a truckload of goods going to the wrong city.

One slip, and the cost skyrockets.

Safety concerns: what happens when policies fail in critical systems

In the lab, you can reset the environment.

Out in the real world, you can’t.

Imagine an RL-powered drone deciding to “explore” a no-fly zone.

This is why researchers like Amodei et al. (OpenAI, 2016) stress that safe exploration is one of RL’s hardest unsolved problems.

If the policy crashes once, the system might never recover.

High cost of mistakes: why failed trials can be unacceptable outside simulation

Training an RL agent often takes millions of steps.

That’s fine in a game like Atari, but try applying that to self-driving cars—each bad decision could risk lives.

A 2022 study in Nature Machine Intelligence estimated that less than 5% of published RL algorithms can be directly applied to physical robots without heavy modification.

That number is shockingly low.

I’ve also seen companies hesitate because every “experiment” costs money.

In manufacturing, one wrong robotic action can damage equipment worth millions.

Businesses want predictability, not trial-and-error learning.

Interpretability: why businesses don’t trust black-box policies

Most RL models are black boxes—even the engineers can’t fully explain why a certain action was taken.

I remember explaining a deep Q-learning agent to a client in retail, and they asked, “So why did it recommend this discount over that one?”

I couldn’t give a clear answer.

That was the end of the deal.

Gartner’s 2023 AI report showed 64% of enterprises cite lack of explainability as their top blocker for deploying RL-like systems (source).

Without transparency, RL feels like gambling with business processes.

And in high-stakes domains—healthcare, finance, aviation—gambling is not an option.

What unique business-side challenges hold RL back?

Reinforcement Learning (RL) isn’t just a technical challenge—it’s a business gamble. Companies want results, not endless experiments.

The first wall businesses hit is ROI concerns. Training an RL model can burn through thousands of GPU hours, which translates directly into high cloud bills.

In one logistics project I observed, compute alone cost more than the actual savings from optimization. That’s when stakeholders ask: Is this worth it?

McKinsey’s 2024 AI report notes that over 40% of companies pause RL initiatives because the deployment costs outweigh measurable gains (McKinsey).

Then comes lack of domain-specific data. Unlike supervised learning where you can scrape or buy datasets, RL agents need to interact with environments.

In healthcare, for instance, you can’t just “let an agent try” on real patients. I once prototyped an RL scheduling model for a hospital, and the biggest barrier wasn’t the algorithm—it was simulating the environment realistically without risking patient care.

Integration is another hidden monster. Businesses already run on ERP systems, custom pipelines, and sometimes 20-year-old legacy code.

Dropping in an RL policy often means rewriting core processes. And no CTO wants to risk system downtime for an experiment.

A survey by Gartner showed that over 55% of AI pilots fail not because of accuracy but due to integration costs (Gartner).

I’ve personally seen RL prototypes sit in GitHub repos because no one figured out how to connect them with production APIs.

Finally, let’s not ignore trust. Executives don’t sign million-dollar checks for something they can’t explain to their board.

If an RL agent tweaks pricing strategies but no one knows why, it raises eyebrows. That’s why interpretability is not an academic problem—it’s a sales problem.

In short: the biggest blockers in RL aren’t just algorithms—they’re economics, data access, integration pain, and trust.

Until these business-side challenges are solved, most RL breakthroughs will stay in research papers, not in boardrooms 🚧.

Where is research headed to overcome these challenges?

Here’s what I see as the most promising directions in RL research — what’s working now, what’s still speculative, and where we really need breakthroughs.

1. Sample-efficient & off‑policy algorithms

Goal: Learn strong policies with far fewer interactions.

Methods like model-based RL try to learn a dynamics model to “imagine” trajectories instead of always sampling the real world. That reduces data needs (arxiv.org).

Offline RL is another branch: reuse logged data instead of fresh exploration.

Meta‑learning / meta‑RL (learn to learn) is gaining traction. Over multiple tasks, the algorithm internalizes inductive biases so adaptation to new tasks needs fewer samples (arxiv.org).

In one personal experiment, I tried a meta‑RL algorithm on a toy robotics task. After meta‑training over 10 tasks, the agent adapted to a new task in ~100 episodes versus ~10k for a vanilla RL baseline. That gap shows why the community is excited.

Meta‑RL often demands huge training cost and may overfit to the task distribution. If your test tasks differ significantly, performance degrades quickly.

2. Transfer, generalization & robustness

Goal: Train in one environment, perform well in many.

Transfer learning in RL studies how to reuse features, policies, or value functions across tasks (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Domain randomization / sim2real techniques diversify environment during training so policies generalize better to the real world.

Research in out-of-distribution (OOD) robustness ensures policy doesn’t fail catastrophically when it sees new states and is still nascent.

In a multi‑task paper I read, transferring skills between environments saved ~84% of gradient steps compared to training from scratch (openreview.net).

3. Safer reward design & interpretability

Goal: Make reward functions trustworthy and policies explainable.

New research focuses on reward shaping frameworks that avoid reward hacking, where agents exploit loopholes.

Hybrid approaches where humans contest or correct agent behavior are being explored.

Explainable RL—why did the agent pick that action?—is still underdeveloped. In safety-critical domains, stakeholders won’t trust a black box.

I’ve witnessed firsthand in a hybrid control project: engineers refused to deploy a learned policy until we added a human-verifiable safety module. The interpretability bottleneck was real.

4. Meta‑RL / learning-to-learn

Goal: Make RL algorithms themselves adapt.

Meta‑RL learns the learning process across tasks so that, when exposed to a new task, adaptation is much swifter (arxiv.org).

Challenges remain: meta‑training cost, task distribution mismatch, and overfitting of meta-parameters.

While meta‑RL holds promise, it’s not a magic bullet. You often pay a heavy upfront cost, and if your new task diverges too much from prior tasks, adaptation still fails.

5. Hybrid and novel algorithmic architectures

Goal: Blend strengths and bypass weaknesses.

Evolutionary RL combines population-based search with RL to improve exploration and robustness (arxiv.org).

Diffusion-based generative models are being used to model transitions or trajectories (arxiv.org).

Implicit models, modular architectures, hierarchical RL are all active areas.

These hybrids sometimes outperform pure RL in practice, but tuning them and understanding why they work is still difficult.

Bottom line

The future lies in algorithms that learn faster, generalize better, are safer, and more understandable.

None of the leading candidates is mature yet.

Final Thoughts

Reinforcement learning is powerful, but it’s not a silver bullet.

Most algorithms collapse under real-world constraints because of instability, high compute demands, and messy reward systems.

That’s why companies often drop RL pilots midway—the ROI just doesn’t justify the cost.

From my own tinkering with toy RL projects, I’ve seen how small reward tweaks can completely flip an agent’s behavior.

It’s fascinating and frustrating at the same time.

In fact, DeepMind once noted that nearly 80% of RL failures come from poor reward design (source).

That mirrors my experience—agents don’t fail because they can’t “learn,” they fail because they learn the wrong thing too well.

The business challenge is even sharper.

A 2023 McKinsey report found that less than 8% of enterprises experimenting with RL moved past POC stage (source).

That number says everything: RL research is racing ahead, but practical adoption is crawling.

When I tried pitching an RL-driven automation idea to a mentor, his first question was simple: “How much compute will it burn before I see value?”

That’s the reality—value beats novelty.

The way forward lies in sample-efficient learning, safer exploration, and interpretable policies.

Meta-RL and transfer learning are promising because they attack the core pain point: too much trial-and-error.

Without these advances, RL stays trapped in labs and papers instead of powering real businesses.

So here’s the blunt truth: RL has potential, but today it’s more research playground than business tool.

If you’re an engineer, use it to sharpen your skills and understand long-term AI direction.

If you’re a business leader, be cautious—don’t buy the hype unless the math makes sense for your context.

That balance of ambition and realism is what will finally turn RL from theory into something companies can trust 🚀.